Mumbet played a significant role in defending the Sedgwick household when Daniel Shay’s men came into Stockbridge.

Mumbet played a significant role in defending the Sedgwick household when Daniel Shay’s men came into Stockbridge.

Here is an excerpt from Catharine Marie Sedgwick’s “Slavery in New England,” which reads in part:

“…The children under her government regarded it, as the Jews did theirs, as a theocracy; and if a divine right were founded upon such ability and fidelity as hers there would be no revolution. Wider abuses make rebels. Soon after the close of the war, there was some resistance to the administration of the newly organised State Government in Massachusetts. Instead of the exemption from taxation which the ignorant had expected, a heavy imposition was necessarily laid upon them, and instead of the licence [sic] they had hoped form liberty, they found themselves fenced in by legal restraints. The Jack Cades banded together; dishonest men misled honest ones; the government was embarrassed; the courts were interrupted; and disorder prevailed throughout the western counties. A man named Shay was the leader; the rising has been dignified as Shay’s war.

There were some skirmishing, and one or two encounters called battles; but with the exception of a few wounds and three or four deaths, it was a bloodless contest–chiefly mischievous for the fright it gave the women, and the licensed forays of the dishonest and idle, who joined the insurgents. Those who had fancied that equality of rights and privileges would make equality of condition; that the mountains and mole-hills of gentle descent, education, and fortune would all sink before the proclamation of a republic, to one level, were grievously disappointed; and the old war was waged that began with the revolt in Heaven, and has been continued down to our day of socialism. The gentlemen were called the “ruffled shirts;” they were made prisoners were ever the insurgents could lay hands upon them; their houses were invaded, and their moveable property unceremoniously seized by those whose might made their right.

Mr. Sedgewick was a member of the state legislature, and absent from his home on duty, at Boston. His family were transferred to a place free from danger or annoyance; all his family, with the exception of the servants, and one young invalid child, Mum-Bett’s pet. Leave her castle she would not, and her particular treasure she felt able to defend. She adopted a rather feminine mode of defence [sic]. She drew bars and bolts, hung over the kitchen first a large kettle of beer, and sound her trump of defiance, the declaration that she would scald to death the first invader.

The insurgents knew she would keep her word, and on that occasion they preserved their distance.

The fear of personal molestation having subsided, the family returned to their home. They were not, however, secure from [?illegible] by the honest insurgents, and thefts by the dishonest. For them all, Mum-Bett has an aristocratic contempt. She did not recognise their “new-made honour,” but accoutered and decked as they were in epaulets and ivy boughs, they were, to her, “Nick Bottom the weaver, Robin Starveling the tailor, Tom Snout the tinker,” &c.

The captain of a company, with two or three subalterns, came to Mr. Sedgwick’s with the intent to capture Jenny Gray, a beautiful young mare, esteemed too spirited for any hand but the master of the family, and “gentle as a dog in his hand,” Mum-Bett would say. So a cowardly serving man obeyed the order to bring jenny Gray from the stable, and saddle and bridle her. Mum-Bett stood at the open house-door, keenly observing the procedure. The captain, with much difficulty, for the animal was snorting and restive, mounted; but whether from an instinct of repulsion, or from some magnetic sign from Mum-Bett (I suspect the latter), she reared and plunged, and threw her unskilled rider on the turf behind her. Again the Captain mounted, and again was thrown; the third time he essayed with like default, then having got some hard bruises, he stood off, and hesitated. While he did so, Mum-Bett started out, unbuckled the saddle, threw it one side, and leading Jenny gray to a gate that opened into a wide field skirting a wooded, unfenced, upland, she lipped of the bridle, clapped Jenny on the side, and whistled her off, and off she went, careering beyond the hope of Captain Smith, the joiner.

Alas! Jenny Gray was not always so fortunate! One dark night she disappeared from the stable, and the last that was seen of her, she was galloping away into the State of New York, bearing one of the Shay leaders from the pursuit of justice.

On another occasion, when a party of marauders were [sic] making their domiciliary visits to the houses of the few gentry in the village, they entered Mr. Sedgwick’s, and demanded the key of the cellar. In those days, the distance now traversed in a few hours was a week’s journey. The supplies of to-morrow, now sent from New York on the order of to-day, were then laid in semi-annually, and Mr. S.’s cellar was furnished for six months’ unstinted hospitality. Mum-Bett led the party, embodying the dignity of the family in her own commanding manner. She adroitly directed their attention first to a store of bottled brown stout. One of the men knocking off the neck of a bottle, took a draught, and pithily expressed his abhorrence of the ‘bitter stuff.’ ‘How should you like what gentlemen like?’ she asked in a tone of derision bitterer than the brown stout. ‘Is there nothing better here?’ they asked. ‘Gentlemen want nothing better,’ she answered with contempt, and they, partly disappointed, but more crestfallen, turned back and left untasted, liquor which they would have been as ready as Caliban to swear was ‘not earthly,’ was ‘celestial liquor.’ She managed her defensive warfare to the end with equal adroitness. She had secreted the watches and few trinkets of the ladies, and small articles of plate, in a large oaken chest containing her own wardrobe; no contemptible store either. Bett had a regal love of the solid and the splendid wear, and to the last of her long life went on accumulating chintzes and silks.

————————————————————————

3. At this point in the story, the spelling of Sedgwick reverts to the way it is spelled today. LLDB.

————————————————————————

When, after tramping through the house, the came to Bett’s locked chest and demanded the key, she lifted up her hands, and laughed in scorn.

“Ah! Sam Cooper,” she said, “you and your fellows are no better than I thought you. You call me ‘wench’ and ‘nigger,’ and you are not above rummaging my chest. You will have to break it open to do it!” Sam Cooper, a quondam broom-peddler (to whom Bett had pointed out, in their progress, his worthless brooms rotting in the cellar) was the leader of the party. “He turned,” she said, “and slunk away like a whipped cur as he was!”….. ”

We have marked a few striking points along the course of her life, but its whole course was like a noble river, that makes rich and glad the dwellers on its borders.

She was a guardian to the childhood, a friend to the maturity, a staff to the old age of those she served. More than once, by a courageous assumption of responsibility, by resisting the absurd medical usages of the time, in denying cold water and fresh air to burning fevers, she saved precious lives.

The time came for leaving even the shadow of service, and she retired to a freehold of her own, which she had purchased with her savings. These had been rather freely used by her only child, and her grandchildren, who, like most of their race, were addicted to festive joys.

In the last act of the drama of life, when conscience upheaves the barren or the bloated past, and poor humanity quails, she met death, not as the dreaded tyrant, but as the angel-messenger of God. Some of the “orthodox” pious felt a technical yet sincere concern for her. Even her worth required the passport of “Church Membership.” The clergyman of the village visited her with the rigors of the old creed, and presenting the terrors of the law, said, “Are you not afraid to meet your God?” “No, Sir,” she replied, calmly and emphatically–“No, Sir. I have tried to do my duty, and I am not afeard!” She had passed from the slavery of spiritual conventionalism into the liberty of the children of God.

She lies now in the village burial ground, in the midst of those she loved and blessed; of those who loved and honoured her. The first ray of the sun, that as it rose over the beautiful hills of Berkshire, was welcomed by her vigilant eye, now greets her grave; its last beam falls on the marble inscribed with the following true words:–

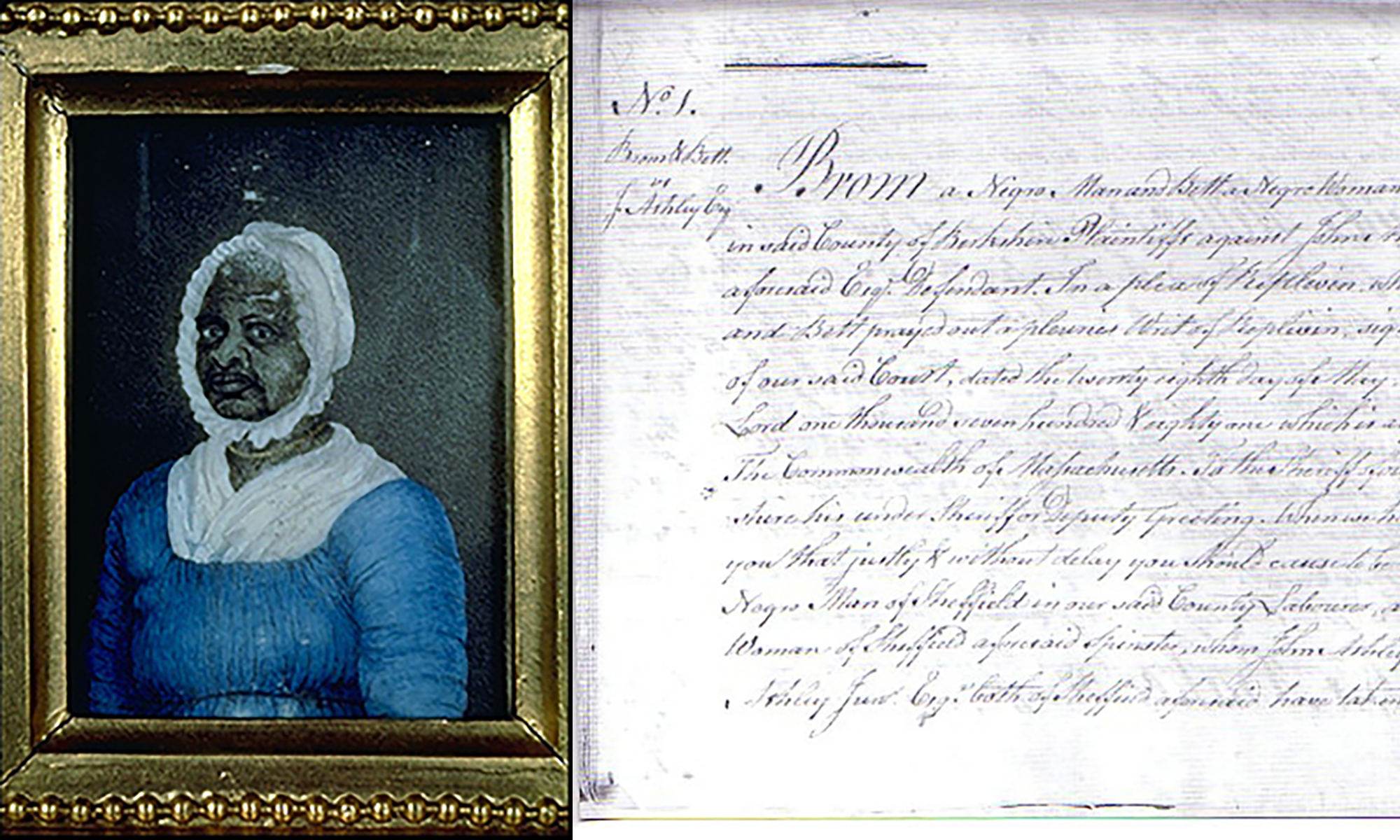

“ELIZABETH FREEMAN,

(known by the name of Mum-Bett),

died Dec. 28th, 1829.

Her supposed age was 85 years.

She was born a slave and remained a slave for nearly thirty years: She could neither read nor write; yet in her own sphere she had neither superior nor equal: She neither wasted time, or property. She never violated a trust, nor failed to perform a duty. In every situation of domestic trial she was the most efficient helper and the tenderest friend. Good mother, farewell!”